By Jeffrey Siger

As published May 21, 2022 12:00 am on the murderiseverywhere blogspot

Saturday-Jeff

Last Wednesday, I had the great honor of participating on a ZOOM panel sponsored by Democrats Abroad Greece (DAGR) addressing the current surge in book banning. Moderated by former US diplomat and author John Brady Kiesling, the panelists included a MacArthur Award-winning poet (Alicia Stallings), the Poet Laureate of Missouri (Aliki Barnstone), a former DJ with a doctorate from Oxford and a reputation for gifted presentations (Abby Hafer), and a kid from Pittsburgh.

This is essentially what the hindmost had to say on banning books:

To put things into perspective, let’s first look at some of the books banned in America.

The most banned book of 2021, and thus far into 2022, is Gender Queer, by Maia Kobabe (a memoir about coming out as non-binary).

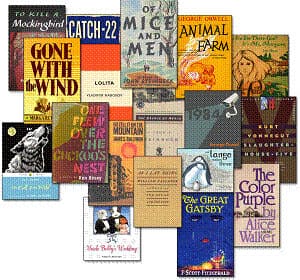

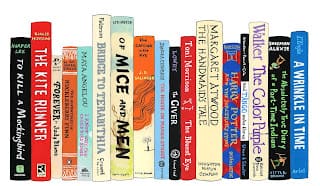

The (arguably) top ten most banned classics of all time (listed 1 to 10):

1984, by George Orwell (social & political themes, sexual content, pro-communism)

Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain (racist, coarse, trashy, inelegant, irreligious, obsolete, inaccurate, and mindless)

The Catcher in the Rye, by J.D. Salinger (foul language)

The Color Purple, by Alice Walker (sexual content, violence and abuse)

The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald (language and sexual references)

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, by Maya Angelou (explicit portrayal rape and other sexual abuse)

The Lord of the Flies, by William Golding (racial profanity, implies man little more than an animal)

Of Mice and Men, by John Steinbeck (violence, racism and treatment of women)

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, by Ken Kesey (glorifies criminal activity, tendency to corrupt juveniles, contains descriptions of bestiality, bizarre violence, torture, dismemberment, death, and human elimination.)

To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee (profanity and racial content)

Examples of other banned books:

Farewell to Arms, by Ernest Hemingway (as a sex novel, and in Italy because of its painfully accurate portrayal of a Fascist retreat)

Call of the Wild, by Jack London (violence, vulgar language, sex)

Leaves of Grass, by Walt Whitman (sexually charged poems)

The Harry Potter series, by J.K. Rowling (promoted witchcraft)

A Thousand Splendid Suns, by Khalid Hosseini (violence and abuse upon women in Afghanistan)

The Handmaid’s Tale, by Margaret Atwood (vulgarity, sexual overtones, LGBTQ themes, offending Christians)

George, by Alex Gino (involvement of transgender child, encourages children to change their bodies with hormones)

The Holy Bible (violates Church & State to buy for schools with public funds, sexual content)

To me, the essence of what’s behind book banning is abject fear on the part of those advocating for a ban that their ideas are too weak to stand up to whatever is written in what they seek to ban.

When you look at any modern list of banned books, literary merit is rarely an issue. Perhaps that’s what frightens book banners the most. They fear they can’t succeed in a reasoned debate over substance, so instead they seek to deny their opposition the opportunity of competing for the hearts and minds of the constituency at issue.

The left sees book banning as cover for hate.

The right sees book banning as a righteous rebellion against times and attitudes different from the way they want them to be.

Book banning is not new, but what makes the current situation so threatening is that those seeking to obtain or maintain political power have seized upon broad-based, well-financed, book banning efforts utilizing extremist buzzwords as the means for galvanizing political support among an already deeply divided electorate. It has nothing to do with the substance of the books and everything to do with gathering support for deeper societal and political agendas.

It’s as simple–or complicated–as that.

Book banning per se didn’t get truly underway until after the invention of the Gutenberg commercial printing press in 1440. Although the Chinee had their own method of printing as early as 868 BCE, the preferred method of dealing with the limited supply of written materials deemed offensive or threatening to the powers-that-be, was to burn them.

Johann Guttenburg

Johann Guttenburg

For example, early in the 3rd Century BCE, the new Chinese emperor ordered the destruction of all books that could serve to compare him to more successful or virtuous rulers of the past.

Throughout history conquerors burned libraries as a means of undermining a conquered people’s society, and European rulers sought to protect their own societies by ordering the destruction works that threatened to spread foreign customs.

Burning of the Library of Alexandra

And of course, differing religious beliefs drove book burnings. Most notably, perhaps, in 1240 in what’s known as the Disputation of Paris, when a challenge brought before the court of King Louis IX by the Catholic Church over how it claimed Jesus was portrayed in Jewish writings led to the destruction of 10,000 volumes of Hebrew manuscripts.

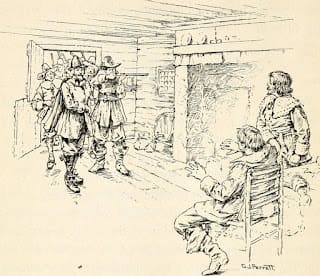

In America, the first actual book banning took place in Massachusetts in 1637 when a man named Thomas Morton published “New English Canaan,” lampooning the Puritans for many things, including their treatment of native peoples. Copies that could be found were destroyed, and those that weren’t were banned. Today it’s considered a classic of Colonial American history and literature.

Arrest of Thomas Morton

But whether the motivation be differing political or religious agendas, the driving force behind attacking a book is to eliminate alternative narratives from the official line and in so doing, control the dialogue.

Authoritarian types have long recognized the danger books posed to their view of the world, for books encourage people to change their way of thinking. Thus, Hitler burned books, so did Mao Zedong.

But in modern times, with so many formats available, book burning has fallen out of fashion, to be replaced by book banning and the like. In America, what once involved arguments made at the local level before school boards, libraries, and PTAs, are today the subject of well-financed legislative efforts.

Today there certainly are subjects one would think merit a ban, but where does one draw the line? For example, you’d think instructions on how to blow up a building, or to properly use an AR-15 to take down the maximum number of targets in the minimum amount of time merit bans—unless of course you’re in the business of razing buildings (that’s with a “z”) or are a combat soldier training to defend your country.

There always will be examples to serve all sides of any argument on the merit of banning books, but in these days of readily available on-line how-to videos on virtually any topic, what’s gained by going after books, except political publicity for the banners and mega-buy-this-book publicity for authors and publishers.

I see no reason to ban any book. If one crosses the line to where civil and criminal laws apply, I say prosecute, because no matter the writer’s literary purpose, the consequences remain the writer’s and the publisher’s to bear…whether the book is banned or not.

My bottom line is simple: I believe books do far more to combat the bad, than undermine the good.

And by the way, considering the likely Streisand Effect* on sales of a banned book, please feel free to BAN MY BOOKS.

–Jeff

* A phenomenon that occurs when an attempt to hide, remove, or censor information has the unintended consequence of increasing awareness of that information.