Brian J Purnell, Bowdoin College and Jeanne Theoharis, Brooklyn College

A southern city has now become synonymous with the ongoing scourge of racism in the United States.

A year ago, white supremacists rallied to “Unite the Right” in Charlottesville, protesting the removal of a Confederate statute.

In the days that followed, two of them, Christopher C. Cantwell and James A. Fields Jr., became quite prominent.

The HBO show “Vice News Tonight” profiled Cantwell in an episode and showed him spouting racist and anti-Semitic slurs and violent fantasies. Fields gained notoriety after he plowed a car into a group of unarmed counterprotesters, killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer.

Today this tragedy defines the nature of modern racism primarily as Southern, embodied in tiki torches, Confederate flags and violent outbursts.

As historians of race in America, we believe that such a one-sided view misses how entrenched, widespread and multi-various racism is and has been across the country.

Jim Crow born in the North

Racism has deep historic roots in the North, making the chaos and violence of Charlottesville part of a national historic phenomenon.

Cantwell was born and raised in Stony Brook, Long Island, and was living in New Hampshire at the time of the march. Fields was born in Boone County, Kentucky, a stone’s throw from Cincinnati, Ohio, and was living in Ohio when he plowed through a crowd.

Jim Crow, the system of laws that advanced segregation and black disenfranchisement, began in the North, not the South, as most Americans believe. Long before the Civil War, northern states like New York, Massachusetts, Ohio, New Jersey and Pennsylvania had legal codes that promoted black people’s racial segregation and political disenfranchisement.

If racism is only pictured in spitting and screaming, in torches and vigilante justice and an allegiance to the Confederacy, many Americans can rest easy, believing they share little responsibility in its perpetuation. But the truth is, Americans all over the country do bear responsibility for racial segregation and inequality.

Studying the long history of the Jim Crow North makes clear to us that there was nothing regional about white supremacy and its upholders. There is a larger landscape of segregation and struggle in the “liberal” North that brings into sharp relief the national character of American apartheid.

Northern racism shaped region

Throughout the 19th century, black and white abolitionists and free black activists challenged the North’s Jim Crow practices and waged war against slavery in the South and the North.

At the same time, Northerners wove Jim Crow racism into the fabric of their social, political and economic lives in ways that shaped the history of the region and the entire nation.

There was broad-based support, North and South, for white supremacy. Abraham Lincoln, who campaigned to stop slavery from spreading outside of the South, barely carried New York state in the elections of 1860 and 1864, for example, but he lost both by a landslide in New York City. Lincoln’s victory in 1864 came with only 50.5 percent of the state’s popular vote.

What’s more, in 1860, New York State voters overwhelmingly supported – 63.6 percent – a referendum to keep universal suffrage rights only for white men.

New York banks loaned Southerners tens of millions of dollars, and New York shipowners provided southern cotton producers with the means to get their products to market. In other words, New York City was sustained by a slave economy. And working-class New Yorkers believed that the abolition of slavery would flood the city with cheap black labor, putting newly arrived immigrants out of work.

‘Promised land that wasn’t’

Malignant racism appeared throughout Northern political, economic, and social life during the 18th and 19th centuries. But the cancerous history of the Jim Crow North metastasized during the mid-20th century.

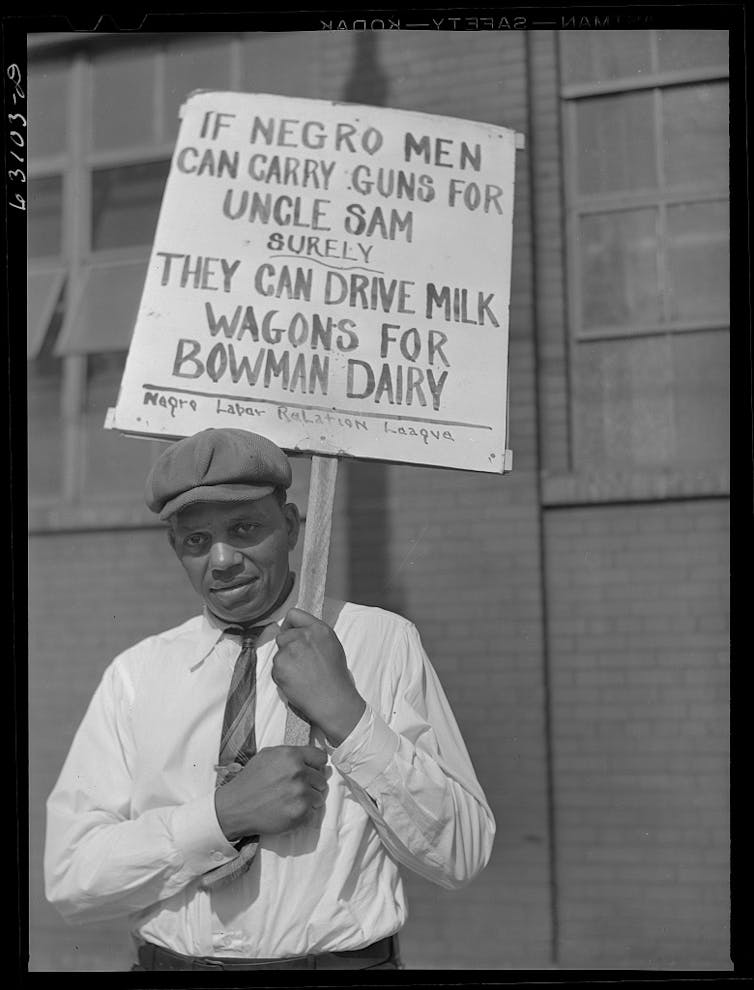

Six million black people moved north and west between 1910 and 1970, seeking jobs, desiring education for their children and fleeing racial terrorism.

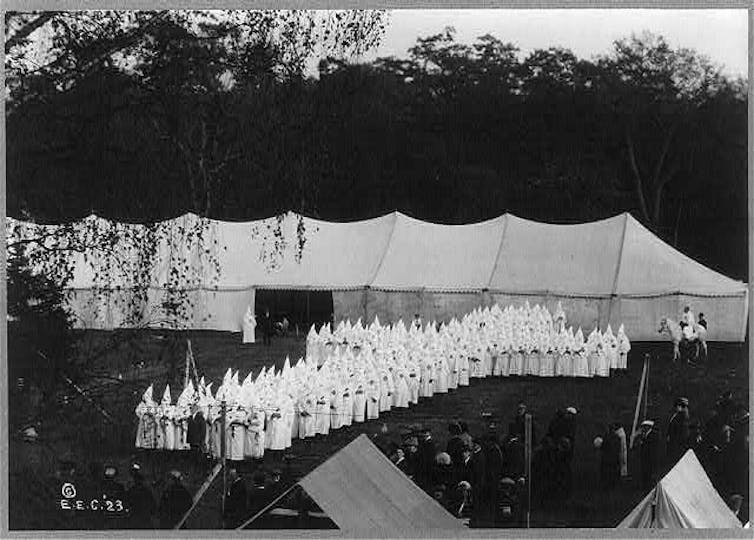

The rejuvenation of the Ku Klux Klan in the early 20th century, promoting pseudo-scientific racism known as “eugenics,” immigration restriction and racial segregation, found supple support in pockets of the North, from California to Michigan to Queens, New York – not only in the states of the old Confederacy.

The KKK was a visible and overt example of widespread Northern racism that remained covert and insidious. Over the course of the 20th century, Northern laws, policies and policing strategies cemented Jim Crow.

In Northern housing, the New Deal-era government Home Owners Loan Corporation maintained and created racially segregated neighborhoods. The research of scholars Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano and Nathan Connolly, through their valuable website, Mapping Inequality, makes this history visible and undeniable.

Zoning policies in the North preserved racial segregation in schools. Discrimination in jobs contributed to economic underdevelopment of businesses and neighborhoods, as well as destabilization of families. Crime statistics became a modern weapon for justifying the criminalization of Northern urban black populations and aggressive forms of policing.

A close examination of the history of the Jim Crow North – what Rosa Parks referred to as the “Northern promised land that wasn’t” – demonstrates how racial discrimination and segregation operated as a system.

Judges, police officers, school board officials and many others created and maintained the scaffolding for a Northern Jim Crow system that hid in plain sight.

New Deal policies, combined with white Americans’ growing apprehension toward the migrants moving from the South to the North, created a systematized raw deal for the country’s black people.

Segregation worsened after the New Deal of the 1930s in multiple ways. For example, Federal Housing Administration policies rated neighborhoods for residential and school racial homogeneity. Aid to Dependent Children carved a requirement for “suitable homes” in discriminatory ways. Policymakers and intellectuals blamed black “cultural pathology” for social disparities.

Fighting back

Faced with these new realities, black people relentlessly and repeatedly challenged Northern racism, building movements from Boston to Milwaukee to Los Angeles. They were often met with the argument that this wasn’t the South. They found it difficult to focus national attention on northern injustice.

As Martin Luther King Jr. pointedly observed in 1965, “As the nation, negro and white, trembled with outrage at police brutality in the South, police misconduct in the North was rationalized, tolerated and usually denied.”

Many Northerners, even ones who pushed for change in the South, were silent and often resistant to change at home. One of the grandest achievements of the modern civil rights movement – the 1964 Civil Rights Act – contained a key loophole to prevent school desegregation from coming to northern communities.

In a New York Times poll in 1964, a majority of New Yorkers thought the civil rights movement had gone too far.

Jim Crow practices unfolded despite supposed “colorblindness” among those who considered themselves liberal. And it evolved not just through Southern conservatism but New Deal and Great Society liberalism as well.

![]()

Understanding racism in America in 2018 means not only examining the long history of racist practices and ideologies in the South but also the long history of racism in the Jim Crow North.

Brian J Purnell, Associate Professor of Africana Studies and History, Bowdoin College and Jeanne Theoharis, Distinguished Professor of Political Science, Brooklyn College

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.